If it seems as though the country music aesthetic is everywhere these days, you’re not wrong. We’re seeing Western wear show up on some of the most significant cultural stages and country is infiltrating a growing number of Spotify playlists.

Pharrell Williams, the music savant and newly minted creative director of Louis Vuitton debuted a cowboy-inspired silhouette for the Vuitton’s fall 2024 menswear collection at Paris Fashion Week in January. Beyoncé appeared at the Grammys with a custom-made jacket from the collection and a white cowboy hat. One of the most talked about performances of Grammy night was the Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs duet of Chapman’s “Fast Car,” which rode to the top of Billboard charts last year thanks to Combs’ refashioned country cover of the song.

PARIS, FRANCE – JANUARY 16: (EDITORIAL USE ONLY – For Non-Editorial use please seek approval from … [+]

Post Malone wore a country-inspired outfit, with a turquoise bolo tie and Wrangler jeans, as he sang a folky-acoustic rendition of “America the Beautiful” just hours before Beyoncé dropped new music from Cowboy Carter — a country-themed album due to release in March. Lana Del Rey announced a forthcoming country album a few weeks prior.

Indeed, country signifiers are creeping into the popular zeitgeist. Be that as it may, although America may be embracing the sound and stylings of country, it doesn’t seem as though country is all too ready to embrace all of America.

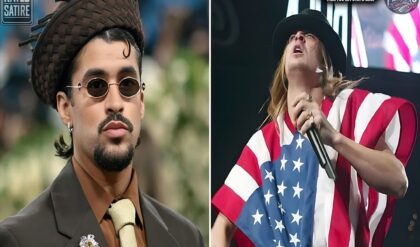

After Beyoncé released two singles post-Super Bowl, “Texas Hold’ Em” and “16 Carriages,” a country radio station in Oklahoma, KYKC refused to play her new music when requested by listeners. The station manager’s rejection was simply: “We do not play Beyoncé on KYKC as we are a country music station.” Not only does this statement dismiss her new releases, but it also denies Beyoncé’s previous forays into country music like 2016’s “Daddy Lessons” from her Lemonade album. It should be noted that this song was the topic of controversy in the country community when she performed live with The Chicks at the 50th Country Music Awards.

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Service, and you acknowledge our Privacy Statement. Forbes is protected by reCAPTCHA, and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

THE 50th ANNUAL CMA AWARDS – The 50th Annual CMA Awards, hosted by Brad Paisley and Carrie … [+]

After hundreds of emails and phone calls from irate fans, KYKC eventually added Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold’ Em” to the rotation. Considering the historical origins of country music, this act of gatekeeping is not merely exclusionary; it is a classic case of cultural appropriation.

Country music has long been considered a genre made by and for white people. However, this conception is empirically false; its roots were heavily influenced by Black music and shaped by Black traditions. The cultural historian and associate professor of critical and comparative studies at the University of Virginia, Karl Hagstrom Miller, puts forth in his work that country music was born from popular music of the South. The genre was a reflection of racially integrated expressions of the time, like jazz and blues, as well as hillbilly and folk practices.

Suffice it to say that country music is Black music because its creation was extracted from Black creators. Its melodies were lifted from hymnals performed in the Black church. Its stylings were borrowed from Black musicians. The banjo, a country music staple, was created by enslaved Africans. The notion of excluding Black people from the genre is not merely preposterous; it’s an act of cultural appropriation.

A man playing a banjo while seated on a stack of crates as a man and a boy listen, US, 1880s. (Photo … [+]

Cultural appropriation occurs when members of one culture take possession or ownership of elements from another group’s cultural identity or associated markers—be it intentional or not. Scholars have categorized cultural appropriation into four types:

- Cultural exchange—the reciprocal exchange of social facts between peer communities of equal power, like the co-creation of hip-hop between Black and Hispanic youths in the South Bronx

- Transculturation—the cultural elements that are co-created from elements of many cultures, like the heterogeneity of U.S. culture

- Cultural dominance—the use of a dominant community’s social facts by a less powerful community, like hip-hop kids adopting skater culture

- Cultural exploitation—the use of a community’s cultural practices and products by a dominant community without reciprocity or permission.

This fourth form of cultural appropriation—cultural exploitation—is the primary target of contemporary critique of which country music’s rejection of Beyoncé and Lil Nas X, for instance, is an exemplar.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA – JANUARY 26: Lil Nas X, winner of Best Music Video and Best Pop Duo/Group … [+]

GETTY IMAGES

Cultural exploitation is a story as old as time. Black productions like sounds, styles, speech, and gestures have been borrowed, imitated, and reworked by white Americans and sold to white audiences without permission from or compensation for Black creators. From swag surfing at the Chiefs game to media outlets attempting to credit Travis Kelce for the fade haircut, this has been an ongoing practice in America. Why would country music be any different? This exploitation of power differentials not only creates an economic disadvantage for Black cultural producers but also erases their existence.

When I first heard the story about Kelce’s fade and its position as his own creation, it made me feel irrelevant. It was as if the scores of people who look like me, who adopted this cultural aesthetic for decades didn’t exist until it was recognized by white America. And when it was recognized, its ownership wasn’t attributed to its creators. It’s harmful. Even Kelce rejected this appropriation by called the misassignment of ownership, “absolutely ridiculous.”

You might ask why a hairstyle would be so personal. It’s more than just a hairstyle; it’s an identity project that reflects who I am and where I’m from; misappropriating its ownership essentially ignores the twenty-some-odd years I wore it. Similarly, to exclude Black people from country music is to ignore the fact that Black people played a prominent role in its creation.

Furthermore, to gatekeep artists like Beyoncé from participating in the genre ignores the fact that she’s from Texas and the country aesthetic is a cultural silhouette of her identity. That doesn’t even factor in the fact that Black people made up a quarter of the cowboy occupation after the Civil War. The redaction of these stories in our cultural folklore supports an enterprise that erases Black people from American history, and this is the part that’s most critical for marketers.

John Dyck of Auburn University suggests that the idea of country music being an exclusive expression of white conventions was simply a marketing vehicle to fashion the genre for a more compelling appeal among white Americans. This construction has effectively excluded Black artists from the genre and instituted an uncredentialled gatekeeping mechanism that polices what’s for “us” even when it’s been made—at least in part—by “us.”

As mass storytellers, marketers have the ability—or dare I say, obligation—to right this ship. We have the platforms, the craft, and the resources to call out exploitation when we see it and ensure the American narrative does not turn its creators into ghostwriters. This is the work we must do as an industry.

I had the privilege to contribute to this work during my tenure at Wieden+Kennedy for our client Courageous Conversations, a nonprofit organization committed to elevating racial consciousness through social discourse. To address the censoring of the Black experience from American history through book bans, Courageous Conversations and the Wieden New York team begged the question: how can we believe in the American dream but erase the dreamers who paved the way for these dreams to be?

This is the exact question we should be asking of country music and its gatekeepers: How can we celebrate the genre without celebrating the creators who paved the way for it to be?